Position Statement: The Part We Play

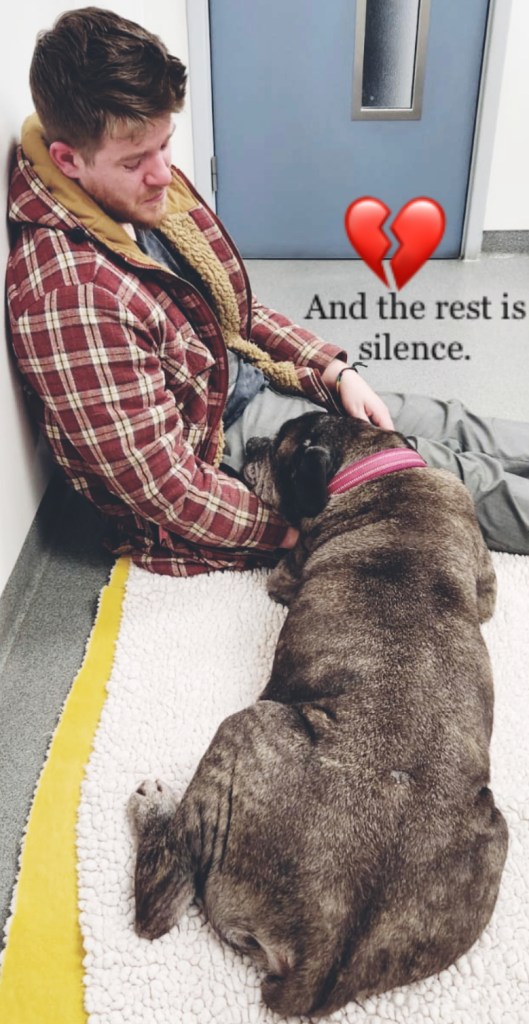

As much as I try to pull myself away from the drama emanating from the online canine community, the Cane Corso is my bosom breed and I just can’t leave it alone. When I first got my Cane Corso, Bonnie, it seemed as though nobody outside of obscure dog fanciers and Italian countryside dwellers had even heard of the breed. By the time she reached the ripe old age of thirteen and departed this earth, last year, the Corso had become the “it” breed.

But with popularity often comes great harm.

Whenever a breed explodes to fame as quickly as this, it comes with serious implications for the dogs. And, by the time of writing, in January 2024, I really do feel like we have done significant harm to the breed – particularly beyond Europe. In our desperation to get in on the action of producing dogs of this “new”, vogue breed, many breeders have failed to import dogs of quality, and have instead often resorted to using semi-related dogs in their foundation stock to bulk out the gene pool… meaning that within a few generations we have (in most countries outside of Italy) oversized, Bullmastiff-esque dogs with Boxer-like jaws coming out of the woodwork, wearing the name of Cane Corso.

And don’t even get me started on what we’re doing to the temperament (but yes, I will address that later, too).

When a breed is new to “the scene”, driving up the numbers is the key to ensuring kennel club recognition, so this trend is hardly surprising. But, when this shaky ground is our foundation, in a country like mine where the breed is in its infancy, pre-Kennel Club affiliation, we are putting our own “spin” on a breed that already has a breed standard firmly established – one that hasn’t needed changing since Antonio Morsiani composed it in the ‘70s, on observation of a very old race of Italian dog. When we fiddle with what’s there, in black and white, we’re producing essentially a new dog under an old (and noble) name.

Okay, but why am I bothered? They’re still beautiful dogs, even if they deviate from the standard, right? Well, yes it’s true that these Bandogges we’re producing are often magnificent… but they are not Cane Corsi. To answer the question of why things as apparently nebulous as weight limits and jaw construction matter so much to me, we need a bit of a history lesson about the origins of these glorious dogs.

Strap in – class is in session.

The History of the “Cane Corso”: Dog of War or Rustic Farmhand?

So, we’ve probably all heard about the “Molossian” ancestry of the Corso – apparently where this dog earned its dubious “war dog” subtitle (despite the mythical Molossus having more in common with livestock guardians than mastiffs or catchdogs). The “molosser” ancestry is all anyone wants to talk about. Honestly, though, it seems like an arbitrary name to give to these dogs, considering that the Molossus dogs were only a snapshot of the Corso’s history – and not even the most impressive… or most “Corso-like”, while we’re at it.

Indeed, before the Molossus, at least eight hundred years before Christ, we can see artistic depictions of ancestral, giant hunting and fighting dogs in Ancient Mesopotamia, and leaner versions a century later, as well as clues about the development of the Alaunt. The apparently iconic (but historically fuzzy) Greek hunting and guarding dogs of the Molossians in the 4th Century B.C. are descendents of these dogs, but were themselves co-opted by the invading Romans a few centuries later and renamed as Canis Pugnaces. The reappropriated dogs of Rome were repurposed and diversified into hounds, catch-dogs and livestock guardians, with only the catch-dogs keeping the name of Pugnaces (i.e. pugnacious, because of their aggressive nature). These catch-dog types of the Romans were later imbued with British steel and violence from the so-called Canis Britanniae dogs encountered over here (themselves likely sharing ancestors with the Molossus). These are the dogs whose image modern mastiff types are redolent of – a long time after the Greeks. So, in the interest of preserving the Roman, rather than Greek, part of the ancestry, why don’t we use the term “pugnax” and call our mastiff-types “Pugs” instead of “Molossers”? Well, I guess because that name was already taken… by another formidable hound.

Anyway, we’re still in the realm of ancestors, here. It’s only after the fall of the Roman Empire that we really start to see the Corso coming into its own. Indeed, it is not the “dog of war” that we see in our modern dog – barely remnants of that already dubious image remain – but rather the versatile catch-dog and farmhand of the centuries following… but I guess that’s not quite as sexy. Do we really want to pay homage to scrappy rural curs when we could invoke the memory of the piriferi, charging into battle with barrels of flaming oil strapped to their backs? Of course not, but we ought to. By the 4th Century, with the end of Rome, the off-cuts of the Pugnax dogs had already become a seamlessly integrated part of the Italian countryside, depicted as boar-hunters in mosaics of the period. For more than a thousand years, the term “Corso” came to refer to the morphologically diverse country dog of the Meridone, with the dogs tasked with everything from hunting game of all sizes, to livestock and pest management, as well as guardianship – excelling in all areas that called for such versatile muscle and ferocity. In the days before “breed” was really a concept (i.e. everything prior to the mid-19th Century in England – and later in other countries), the term Cane Corso was not so much a noun for referring to a breed as it was an adjective used to describe the athletic, powerful, feisty, jack-of-all-trades race of working dogs of Southern Italy.

By the 20th Century, a decline in agricultural dependency and two world wars (wars that notably made no use of these so-called “war dogs”) resulted in a severe decline in Cane Corso numbers – so much so that it seemed the Age of Dog was over in Italy. And it might’ve been, were it not for the idealism of Italian fancier Giovanni Bonnetti, who was so inspired by the idea of the rare Pugliese variety of presa (or “catch”) dogs he’d read about that he recruited the eminent canine researcher, Dr Paolo Breber, to help rescue the breed in the early ‘70s. Stefano Gandolfi, a teenager at the time and an early breed fancier, got wind of Breber’s efforts and enlisted the Malavasi brothers of Mantua, who were German Shepherd breeders before this point, and before long, together they had gathered specimens of the true Cane Corso type as they saw it in Italy. From these, they bred the famous litter that gave rise to “Basir”, the dog upon whom the original breed standard was based, down to precise measurements and ratios, recorded in mathematical detail.

Because Italy already recognised a native mastiff-type, with guarding potential, the Neapolitan Mastiff (or Mastino Napoletano, the Cane Corso’s close relative), it was crucial that the Cane Corso be a distinct dog: one with a scissors bite, to catch with, and one with the perfect balance of size and agility, to chase with – and, of course, the functional design (from structure to coat) to resist the often harsh climate in which it worked: hot summers and cold winters, and onerously long working days.

The Present Picture: Clinging to an Enigma

So, now we find ourselves looking to preserve a breed, in the 21st Century. If this dog is to remain distinct from all the dogs that are similar – the fellow mastiff-types, the other catch-dogs, the similarly muscled and broad-skulled bull breeds – then its standard must be maintained. Most members of the general population can identify a Corso by nothing more than its black coat (which isn’t universal) and its cropped-and-docked status (which is not only not universal but not even legal in countries like mine). Actually, most members of the general population couldn’t pick a Corso out of a line-up of Labradors, but let’s just say for illustration purposes that there is any sense of the dog in the populace. One consequence of us already beginning to lose “type” in these dogs is that they are becoming conflated with American Bullies and the bite statistics there are damaging our breed’s reputation (the American Bully XL has just been banned here in the UK, becoming the first breed added to the Dangerous Dogs Act since 1991). The Corso bite statistics, when actually applicable to our breed and not attributed due to breed confusion, are also a result of awful breeding in terms of temperament (and the wrong homes taking on the dog), but I’ll come to that later.

First, let’s discuss why those physical features (jaw, size, coat) that I’ve focused on are the cornerstone of breed preservation from a morphological perspective.

Jaw

First, let’s consider teeth. Without a clean scissors-bite, the dog is no longer a catch-dog and might as well be any other type of bulldog: a broad head, some chiselled muscle, indistinct size… bear in mind, indeed, that the American Pitbull Terrier is actually a working catch-dog and as such has a beautiful bite. Now, modern Cane Corso breed standards have encouraged mild undershooting of the lower jaw, and to some extent this is acceptable from a functional perspective… but the less this is emphasised the better. We have already reduced the capacity of the Boxer population this way; let’s not allow the same in the Corso. Scissors-bites are functional for the “catch-and-hold” for which catch-dogs are bred. The temperament of the catch-dog may well be less desirable outside of working conditions, but the structure of the muzzle is what ensures the overall soundness of the head: allowing not only for the distinct shape that marks breed type, but more crucially for proper chewing and for sufficient airflow to maintain a safe temperature during long hours of exertion. Modern Bulldogs overheat; their ancestors did not. Again, let’s not let the same happen to the modern Corso.

And that leads us on to size.

Size

The larger the dog, the more difficult temperature regulation can be, particularly if not built with temperature regulating hardware like dolichocephalic skulls and low fat storage, meaning the resultant dog becomes essentially partially disabled by its great mass. But it’s not just about keeping cool. It’s also about functionality in the literal sense. These are historically fast and powerful dogs. Significant mass is required to exert force, but the larger they become beyond this point, the slower they get. This is not just a cliché about size, but a matter of science. Let’s consider in abstract terms first why making a larger dog on the same structure is inevitably going to lead to a slower dog. When you consider a horse, a larger animal by far, you have no doubt that it is faster than a Cane Corso; but when you consider a Mastiff (of the Old English variety, capital M), only a trivially larger animal within the same species, you have no doubt that it is slower than the Corso. Why is that? Well, it’s because when you add bone and muscle mass to an existing structure (i.e. the molossoid type), it’s like strapping sandbags onto your dog – whereas a horse has an entirely different structure: leggier, with larger hearts and lungs, and a retracted abdomen, designed for performance at that great size. If we are to maintain our dog’s structure (by which I mean NOT outcrossing to Greyhounds to change the habitus) then adding size is a surefire way of restricting its capacity to perform as an athlete.

There’s the abstract; now for the science.

If we think about it biologically, we have two types of tissues in animal bodies: active and passive. In effect, we have tissues that can produce force and therefore generate speed (predominantly the muscles), and we have tissues that just come along for the ride (the bones, most of the organs, the skin, the fat, the coat, etc.). When we increase muscle (active tissue), we can’t do that without bringing along all that dead weight (the passive tissue) in the growth process – and we have very little control over the ratio of active-to-passive tissue acquisition. That said, if we could, through the use of anabolic steroids, or myostatin inhibition, emphasise the development of active tissues in our “supersizing” efforts, we would create mega muscular dogs… but they’d still not be much faster. That’s because of the second complicator: not all muscle is functional. Myostatin exists to inhibit the production of nonfunctional muscle mass – inhibiting it does not aid in sprinting capacity. In short, even muscle has diminishing returns and will lead to slower dogs before long. But it goes even deeper than that, because we’re not only producing slower dogs by adding mass, we’re also creating less POWERFUL dogs. That sounds unbelievable, I know, looking at the projected hulking structure… so, let’s look at some physics to explore why that is.

Okay, so, the formula for calculating kinetic energy (i.e. punch power) is ½MV^2, where M is Mass and V is Velocity. If we take a Corso at the lower end of the standard — a 40-kilo dog running at a top speed of about 30 miles per hour (converted from miles per second for ease) — and a Corso at the upper end of the standard (a 50-kilo dog running at a top speed of about 25 miles per hour, because we already know they are slower), and multiply the resultant Joules using the coefficient of 9.81 to establish energy in kilogram-force metres, we end up with the 20%-lighter, 15-ish-%-faster dog hitting its target with a massive 80 kilogram-metres or so more impact force! (It’s worth mentioning that your typical greyhound would produce another 80-odd more kilograms of impact… but would lack the size to finish the job on large game – so it’s always a balance). If the Corso were purely a guardian, like its hefty cousin the Mastino, with nearly twice the mass and a little over half the running speed by my estimates, this slow-down and impact-reduction that accompanies the size increase wouldn’t be an issue. But the Corso is a dog of action first, and a sentry guardian second. Wherever you consider the “start” of the Cane Corso as a fixed type to be – ancient dog of war, historical hunter of game, or emergent show dog of the ‘70s – its “medium-large” size (as per the standard) is of crucial importance to its function and distinction from its mastiff-type cousins. It is, in short, the perfect balance between size and speed.

Now, as a major disclaimer: when we do have rare, larger specimens who are structurally sound, whose growth has been in proportion and who can move well, we should not dismiss them out of hand – I want to be clear on that – but, we should call it what it is: an anomaly, a variant, an outlier. If they arose naturally in the Meridone a few centuries ago, they would simply be tasked with different work, not culled. We should not be deliberately breeding towards the 60-kilo-plus Cane Corso, but nevertheless should accept these outliers as naturally occasioned, beautiful giants – a result of a gradually increasing gene pool and the natural consequence of a greater sample size of dogs and better prosperity in terms of nutrition and healthcare these days. Indeed, if we have a few more of these dogs arising naturally in standard-focused breeding programmes, we may inject a little necessary beef into the gene pool and see more Corsi with enough bone and substance to justify their molossoid categorisation – because the opposite direction (shrinking and leaning out dogs to the extent of having dwarf-Weimaraner clones trotting about the Corso’s show ring) is just as undesirable, and on the rise in some places!

It’s about breeding to a standard, not breeding for size.

Colour

Now, onto colour. It may surprise you to hear that I care very little about colour. It doesn’t bother me that most people refer to the “grey” colour from the standard as “blue” – or rather, it doesn’t bother me when owners say it. I do feel like breeders should be intimately familiar with the breed standard of their dog, so a breeder advertising “blue” dogs is a minor red flag… but still, no major concerns. Similarly, I’m not bothered if you spell “formentino” in the traditional Italian (i.e. FROmentino) or not. The coat colour, and its naming, is of very little importance outside of the show ring. It would, in fact, be of TOTAL irrelevance to me if it were not becoming indicative of blatant crossbreeding under the name of Cane Corso – and sadly, with so-called “white” dogs (with no sign of albinism), and much more commonly with “Merle” specimens, this is becoming the case. The coat anomalies – whilst only supposed to be a method for attracting buyers looking for a “rare” Corso (as if your own dog isn’t already going to be the rarest of all loves, it being yours) – has belied the “purebred” status these dogs claim.

So, no, to be clear: the Merle gene is not present in the Corso’s genome – and never has been. A Merle Cane Corso does not exist.

Should we care about the pattern from a visual perspective? No. But, when it comes to genetics, unfortunately, aesthetics are the least of our concerns. Whilst some breeds in which the Merle gene naturally occurs, such as the Catahoula Leopard Dog, are less at risk – and the Piebald gene poses more of a risk than Merle does – it is still crucial to note that the single Merle gene is associated with modestly higher rates of deafness and visual issues in dogs… and dramatically higher rates of both in “Double-Merles” (dogs for whom both parents carry the gene). Breeders who produce so-called “Merle” Cane Corsi have irrefutably used other breeds (likely Great Danes) in their breeding programmes to deliberately promote inheritance of that trait (and bear in mind that Danes also frequently carry a double-dose of risk, as Piebald often co-occurs with Merle in the breed), meaning the offspring are in jeopardy. Now, can we minimise that risk by avoiding the pairing of two Merle dogs together? Yes. Will the types of breeders who select for this trait do that, in the interest of the dogs’ health? Hell no. Selling “rare” Corsi is a money game for them – I won’t move on that. What’s more, even if they tried, it’s not surefire; Single-Merles still carry elevated risk, AND in the absence of genetic testing, you can’t always identify Merles – as is the case for so-called “hidden Merle” and “cryptic Merle” dogs, who carry the gene but don’t express it in a way we can visually ascertain – so it’s out of your hands.

So, be smart: don’t call a “Merle” crossbreed a Cane Corso purebred if you own one – and don’t add it to your breeding programme if you produce Corsi.

On the subject of colour, it’s worth noting that black is by far the most popular colour for owners outside of the showing and working world. I can only assume this is due to the striking visual effect that an all-black dog can give – almost panther-like in beauty and presence. It’s also likely influenced by the fact that none of the similar-looking dogs (Dogos, Presas, Bullmastiffs, etc.) have solid black in their palette – and so a black coat can help to compensate for an absence of type, as I mentioned a minute ago (particularly in countries like England where ear-cropping, another hallmark of the breed, is banned) – i.e. making a Corso look like a Corso when it otherwise doesn’t meet the standard. However, by disproportionately selecting for black dogs, are we driving down the longevity of our breed? The research on Corso lifespan indicates that brindle dogs live an average of a year longer than the solid black dogs – and the oldest black-brindle dog in the same study outlived the oldest solid black dog by two whole years. (My Bonnie, who lived to the ripe old age of 13, was black-brindle, too.) A diverse gene pool is always going to improve lifespan, in general, but when we know about the specific genetic links between brindling and longevity, it may be worth being more permissive of dogs that aren’t just pure black. Just a passing thought! I have my biases, too, of course!

Okay, now onto the stuff that really matters. It’s time to talk: Corso temperament.

The Cane Corso Temperament: A Measured Guardian

The true Cane Corso is what I call an “alpha” dog, but not in the stupid sense. In the literal sense, the Cane Corso exudes alpha from every pore… true Big-D-energy – even in the females. A Corso does not need to be demonstrative with its power; it is a quietly confident, collected, stable dog. It does not demand respect, but rather assumes it. As a family companion, the Corso is gentle, tolerant, and forever close-by. As a guardian, the Corso is simply aloof and uninterested in strangers – unless they are unfamiliar and encroaching on the family’s territory. In those cases, a good Corso is proportionately vocal, positioning itself between the threat and what it protects – be it family or the family home – and remaining there, using spatial pressure and barking, rather than force, to prevent the intruders access. It is rare for a true Corso to bite a human, unless trained in bitework and given the command. This is crucial for the breed’s survival in modern society.

I could go on and on – and write a love letter to the Cane Corso’s temperament – but that’s not the focus of this article. What I’m interested in (concerned about, really!), today, is where the temperament has been maligned and misdirected. Here are a few examples of what I have heard, both online and in person, referred to as cases of “Corsos being Corsos”:

- Scrambling past their owners to get to the front door when a visitor has arrived, to “see them off”, lunging and snapping (and sometimes making contact!).

- Snarling, growling, and staring at visitors who have been permitted entry to the home by the owner (and sometimes needing to be physically restrained or confined).

- Growling, barking, and lunging at strangers when out-and-about, away from the family home (and sometimes biting or attempting to bite).

AND… - MOST CONCERNINGLY: “Protecting” one member of the family from others in the family, especially a child, and not permitting their loved ones access to that individual.

Spoiler: none of those things are consistent with the Cane Corso’s true temperament. They are in fact indications of insecurity and excess aggression. These behaviours are not just the dog’s “protective instincts kicking in”, as so many assume, given their sudden manifestation during and after adolescence. Instead, they are usually a result of poor socialisation and generally insufficient canine husbandry – and occasionally the result of innate genetic tendencies due to poor breeding. A protective Corso is never unduly aggressive – indeed, the most stable specimens save their bark for legitimate instances of unfamiliar aggressors with an apparent potential of harm – and save their bite for absolute disaster scenarios.

They are superb guardians not because of violence but because of vigilance.

Now, why do the individual families whose Corsi have turned into problem-children matter to me? I’m not the behaviourist going out to help them, or taking their dog in for a board-and-train, and my focus is the breed overall – so why do I care?

Well, because reputation matters. If cases like those I just mentioned come to dominate the online world (which they’re already on their way to doing), then two things happen:

- Owners permit this kind of behaviour in their own dogs because it’s perceived as the norm, and so the cycle repeats, both in terms of reputation and the donation of genetic material and parental behaviour modelling to these dogs’ offspring.

- Backyard breeders interpret this permissive attitude to dangerous behaviour as a demand for it… and they supply it, breeding unstable and aggressive dogs to anxious and reactive dogs, and disseminating the litter into the populace, poisoning the gene pool.

In short, accepting this awful behaviour in the Corso breed will only make the problems more common, both at a behavioural and then at a genetic level. We need to insist on absolute stability in our Cane Corsi and the Corsi of others, before our glorious breed becomes the next XL Bully – i.e. a banned breed and a scapegoat for unscrupulous breeders and buyers who want volatile and dangerous dogs to compensate for their tiny genitalia.

Yep, I said it. If you want a genetic mess of a dog to go around and intimidate people with, you’re a Class-A moron. If you insist on having a powerful dog, but have no legitimate need for a protection service dog, then please: get your hands on a supermutt, and back off my breed. Or, preferably, get a grip.

If, on the other hand, you’re like me, and you want to preserve the Cane Corso as the magnificent and noble breed that it once was – and still can be – then please: promote good examples of the dog, and insist on top quality in all fields. We might never outnumber the people who want to destroy the breed with their own selfishness – wanting the biggest dog, the one with the rare coat pattern, the one that will mess up anyone they don’t like – but we can outsmart them, putting our perfect examples out there for all to see, educating the uninitiated, to beat the rising tide of negative stereotypes about our breed.

Let’s go and make a change.

As always, this post is dedicated to Bonnie: the Cane Corso who started it all for me; the Cane Corso who changed my life, who saved my life. Rest in peace, girl.